Protein’s Role in the Body

While protein is often associated with building lean muscle, its smaller components, polypeptides and amino acids, are essential for countless bodily functions from immune system support and hormone regulation to energy production and fluid balance. To ensure the body can create functional proteins while maintaining lean body mass, adequate protein intake is critical or we will suffer the consequences of protein deficiency.

But how much protein do you need each day? This depends on many factors, including age, activity level, and body composition, along with any health conditions. In this guide, we’ll explore how to calculate your protein needs and explain why it’s more complex than just a single number.

Understanding Protein Requirements

Amino acids play many roles in the body. They are used to build bodily structures, enable communication between cells, make critical compounds like serotonin and glutathione, and create energy. Your body is continuously creating and destroying proteins, a process known as protein turnover. This dynamic process, which shifts from anabolic (building up) to catabolic (breaking down) as we age, ensures that proteins are available as needed and that misfolded, aged, or damaged proteins and excess amino acids are eliminated.

Traditionally, nitrogen balance—a measure of the nitrogen (i.e., protein) consumed versus exreted in sweat, urine, etc.—has been used to determine protein needs. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) uses this to set the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR), the average intake level estimated to meet the needs of half of the healthy adults. But nitrogen balance assumes that the sole purpose of consuming protein is to use the amino acids in nitrogen-containing molecules, which isn’t the whole story. Higher intakes of some amino acids may yield benefits such as enhanced growth and maintenance of lean body mass, greater satiety, increased calorie burn, better glycemic regulation, and faster recovery time after illness or injury.

Because there’s no perfect method to pinpoint the amount of protein needed for all these functions, several calculations are used to estimate individual needs.

Calculating Daily Protein Requirements

The most common method to estimate daily protein needs is to multiply body weight by a multiplier that takes age, activity level, and health status into account. For example, the IOM’s Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA), that is the amount that meets the needs of nearly all healthy adults, is 0.3–0.36 grams of protein per pound (0.66-0.8 grams per kilogram) of total body weight.

However, research shows that many people achieve better health outcomes when consuming larger amounts of protein than the RDA identifies. People who are physically active need more protein than those who are not, even at the same body weight. Exercise increases the demand for protein to support muscle mass and mitochondrial function, as well as enhancing immune and hormonal responses. As well, older adults need more protein to prevent muscle loss as do people assigned female at birth who are experiencing perimenopause or menopause who have not yet reached 60 years of age.

In addition to proving that certain individuals have higher protein needs—such as athletes, older adults, or those with certain health conditions, research has consistently shown that using total body weight poorly estimates the amount of protein many individuals need. Using lean body mass (fat free mass) with a multiplier to calculate protein needs often provides a more accurate estimation of protein needs, as the focus is on the most metabolically active tissue.

Alternatively, you can calculate protein needs as a percentage of calories consumed. The IOM’s Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) for protein is 10-35%, meaning that the calories consumed from protein-rich foods should be 10-35% of total calories consumed. According to the IOM, using the AMDR does not negate the need for an individual to meet the RDA for protein, but does not provide further guidance on when to use the higher percentages. As well, the percentage of calories from protein must be considered in relation to the percentage of calories from fat (20-35%) and carbohydrates (45-65%) to reduce the risk of chronic disease, while ensuring adequate intake of essential nutrients.

Special Considerations

People who are pregnant must consume enough protein to meet their own needs, as well as the needs of the growing fetus. In early pregnancy, the increased protein needs are mainly the birthing parent’s as they experience an increased in blood volume and tissue growth, including placental creation. Later in pregnancy, the growing fetus accounts for the majority of the increase in protein needs. According to the IOM, an additional 10 grams of protein per day will meet the increased requirements throughout pregnancy. However, some research shows that this is an underestimation and recommend a multiplier based on body weight, as defined below. Breastfeeding and chestfeeding also require higher protein intakes by the feeding parent for the first six months postpartum.

Acute care and ICU patients also have increased protein needs as their bodies fight to recover from illness, injury, physical trauma, burns, or surgery. As well, some chronic conditions, such as kidney disease, liver disease, and some cancers, may require an adjustment to daily protein intake. If you or someone you love is dealing with an acute or chronic condition, please work with the appropriate healthcare provider to determine the adequate protein intake level.

How to Calculate Protein Needs by Weight

First, choose the most accurate weight measure for your situation:

- Total Body Weight (TBW): For individuals with a healthy body mass index (BMI = 18.5 – 24.9) or active individuals who are classified as overweight (BMI = 25.0 – 29.9) due to their higher muscle mass.

- Ideal Body Weight (IBW): For people who are underweight (BMI < 18.5), sedentary (i.e., those who don’t exercise), or classified as overweight or obese by BMI (BMI = 25.0 and above).

- Adjusted Body Weight (ABW): For those with a higher BMI, ABW takes into account the small amount fat tissue contributes to metabolism.

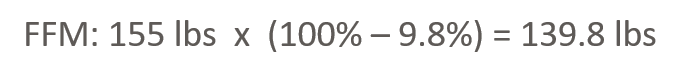

- Fat Free Mass (FFM): The most precise measure, FFM excludes body fat and calculates need based on lean tissue alone.

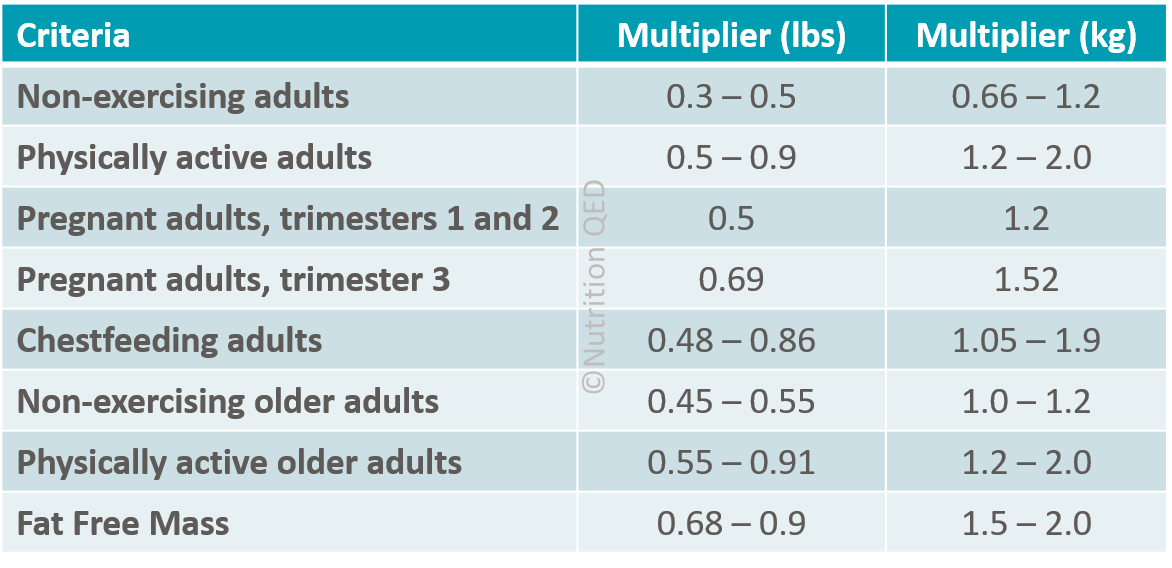

Once you determine your weight by the measure chosen above, use the following multiplier table, being sure to select the multiplier for the unit—pounds or kilograms—used in the weight calculation:

The equation used for the weight and the multiplier is as follows:

How to Calculate Protein Needs by Calorie Consumption

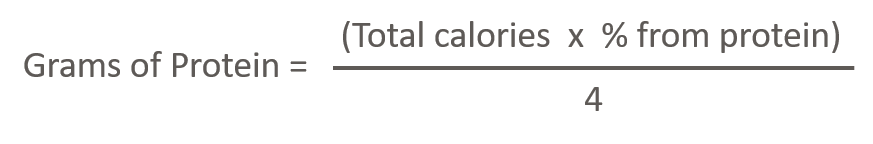

Start with the number of calories consumed or needed to achieve a goal weight. Then determine the percentage of calories from protein in the range of 10-35%. Now use the following equation, which includes the conversion from calories to grams:

As with the calculation involving weight and a multiplier, you may decide to choose a higher percentage based on your activity level, age, and current health status.

Examples of Protein Needs

Scenario 1: Non-exercising adult in menopause

Daily protein needs for a non-exercising adult, age: 50, height: 5’5”, weight: 140 lbs, BMI: 23.4, menstruating status: menopause, estimated caloric needs: 1,700

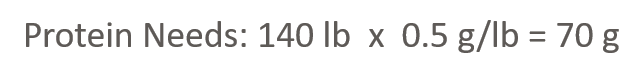

Because this individual does not exercise, is menopausal, and has a BMI in the healthy range, a multiplier of 0.5 grams / pound is selected:

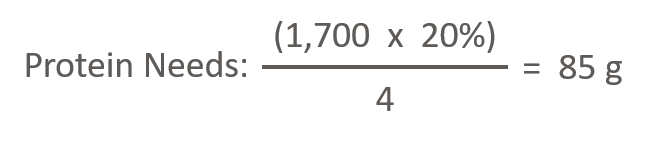

To calculate this individual’s protein requirements as a percentage of calories, 20% is selected:

Based on these calculations, this person will likely meet their body’s protein needs by consuming 70 – 85 grams of protein each day.

Scenario 2: Active woman in her thirties

Daily protein needs for an active woman, age: 35, height: 5’10”, weight: 195 lbs, BMI: 28.1, menstruating status: menstruating, estimated caloric needs: 2,300

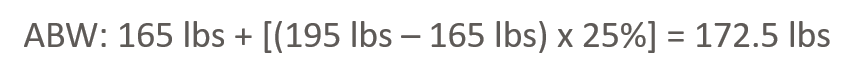

Because this individual is classified as overweight according to BMI and she desires to lose some weight, an Adjusted Body Weight (ABW) will be calculated using the Ideal Body Weight (IBW) of 165 pounds.

Using the ABW and a multiplier of 0.7 g/lb to fuel her active lifestyle, her protein needs are estimated as:

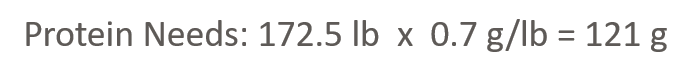

To calculate her protein requirements as a percentage of calories, 30% is selected:

Based on these calculations, this person will likely meet their body’s protein needs by consuming 121 – 173 grams of protein each day.

Scenario 3: Older adult bodybuilder

Daily protein needs for a male bodybuilder, age: 60, height: 5’8”, weight: 155 lbs, BMI: 23.7, Body Fat Percentage: 9.8%, menstruating status: N/A, estimated caloric needs: 2,600

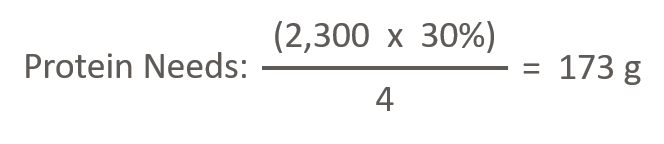

Using his measure for Body Fat Percentage, first his Fat Free Mass (FFM) is calculated:

To maintain muscle and promote growth, a multiplier of 0.8 grams / pound will be used with the FFM:

Since calculations using Fat Free Mass give the most accurate estimate of protein needs, no calculation involving calories is performed.

This individual will likely meet their body’s protein needs by consuming approximately 112 grams of protein each day.

These three scenarios highlight how significantly protein needs can vary between individuals based on age, stage of life, body composition, and activity level. As well, the calculations reveal that calculating daily protein requirements is not black and white. When calculating how much protein you need per day, applying your intelligence and intuition to the results will best determine the amount of protein for your body.

Monitoring and Adjusting Intake

Because calculating protein needs is not an exact science and needs change over time, it’s important to monitor oneself for signs indicating protein sufficiency.

Protein deficiency can affect everything from the hair on our heads to our toe nails. Signs that potentially indicate inadequate protein intake include:

- Fingernails that are brittle, dull, have vertical ridging (from nailbed to tip), or leukonychia (white discoloration of the nail plate)

- Hair that breaks easily, lacks shine, is thin or sparse, or falls out easily

- Trouble thinking or concentrating

- Depression and other mood disorders

- Loss of lean muscle mass or strength

- Stress factures

- Edema—swelling especially in the abdomen, legs and feet

- Getting sick more frequently

- Poor blood sugar regulation

- Being underweight or unable to gain wait

- Poor or delayed wound healing

- Loss of elasticity in skin

- Hearing loss or tinnitus

- Inflammation of the mouth or lips

- Hypothyroidism

- Fatty liver

- Anemia

- Fatigue

Be aware that low stomach acid or protease levels can hinder the body’s ability to effectively digest and absorb protein. Therefore, people with decreased stomach acid and those on acid blockers may be consuming enough protein, but not absorbing it and may have one or more of the above signs and symptoms.

Although the body has mechanisms for using or removing excess amino acids, excessive protein intake for an extended period of time can have detrimental effects in the body. Signs of excessive protein intake include:

- Dehydration or constantly needing to urinate

- Digestive issues such as bloating, constipation or diarrhea

- Weakened bones and bone fractures

- Loss of calcium in urine

- Decreased kidney function

- Kidney stones

- Weight gain, not related to muscle growth

- Inflammation

- Increased blood cholesterol levels

- Heart disease, especially when consuming excessive animal proteins

- Certain types of cancer, such as colon and breast cancer, particularly with high intakes of red meat and processed meats

Body changes are inevitable as we go through the seasons of life. Monitoring for these symptoms and adjusting your protein intake accordingly is key to long-term health.

Conclusion

Understanding your protein needs is vital to supporting various bodily functions beyond just muscle growth. Protein is crucial for immune health, hormone balance, energy production, and maintaining lean body mass. Meeting your daily protein needs not only helps prevent muscle loss, especially as you age, but also promotes overall well-being. However, calculating your protein requirements is not always straightforward, as it depends on your body composition, activity level, and health status.

By learning how to tailor your intake through the strategies discussed—whether you’re calculating by body weight, lean mass, or calories—you can ensure that your body gets the protein it needs to thrive.

To help you navigate this more easily, my guide, “Mastering Your Protein Needs: A Comprehensive Guide,” provides step-by-step instructions, practical lookup tables, and examples of protein-rich meals. Head over to my shop page to purchase your copy today and start taking charge of your nutrition!

Note:

Adequate protein and/or amino acid intake alone is not sufficient to maintain or delay loss of muscle mass and strength in adulthood. Exercise is a necessary component of muscle preservation as it stimulates muscle protein synthesis, thereby triggering the body to use the ingested protein to create lean body mass.

Image from Pixabay.

Sources:

Antonio J, Candow DG, Forbes SC, Ormsbee MJ, Saracino PG, Roberts J. Effects of Dietary Protein on Body Composition in Exercising Individuals. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1890. Published 2020 Jun 25. doi:10.3390/nu12061890

Axe J. 10 Protein deficiency Symptoms, plus Causes, Treatments, more – Dr. Axe. Dr. Axe. Published April 8, 2024. Accessed September 6, 2024. https://draxe.com/nutrition/protein-deficiency/

Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):542-559. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.021

Baum JI, Kim IY, Wolfe RR. Protein consumption and the elderly: What is the optimal level of intake? Nutrients. 2016;8(6):359. Published 2016 Jun 8. doi:10.3390/nu8060359

Centers for Disease Control. BMI frequently asked questions. BMI. Published June 28, 2024. Accessed September 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/bmi/faq/

De Waele E, Jakubowski JR, Stocker R, Wischmeyer PE. Review of evolution and current status of protein requirements and provision in acute illness and critical care. Clinical Nutrition. 2021;40(5):2958-2973. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2020.12.032

Dekker IM, Van Rijssen NM, Verreijen A, et al. Calculation of protein requirements; a comparison of calculations based on bodyweight and fat free mass. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2022;48:378-385. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2022.01.014

Delimaris I. Adverse Effects Associated with Protein Intake above the Recommended Dietary Allowance for Adults. ISRN Nutrition. 2013;2013:1-6. doi:10.5402/2013/126929

Dickerson R. Nitrogen balance and protein requirements for critically ill older patients. Nutrients. 2016;8(4):226. doi:10.3390/nu8040226

Elango R, Ball RO. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements during Pregnancy. Advances in Nutrition. 2016;7(4):839S-844S. doi:10.3945/an.115.011817

Fox VJ, Miller J, McClung M. Nutritional support in the critically injured. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 2004;16(4):559-569. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2004.06.003

Garcia MC MD. Are you getting enough protein? Here’s what happens if you don’t. UCLA Health. Published November 14, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2024. https://www.uclahealth.org/news/article/are-you-getting-enough-protein-heres-what-happens-if-you-dont

Geisler C, Prado C, Müller M. Inadequacy of Body Weight-Based Recommendations for Individual Protein Intake—Lessons from Body Composition Analysis. Nutrients. 2016;9(1):23. doi:10.3390/nu9010023

Hamdy O MD PhD, Committee OPGM Chair, Clinical Oversight, Cde MMMe Rd, Facp R a. GM PhD,, Committee TM of the JCO. CHAPTER 2. Clinical Nutrition Guideline for overweight and obese adults with Type 2 diabetes (T2D) or prediabetes, or those at high risk for developing T2D. AJMC. https://www.ajmc.com/view/chapter-2-clinical-nutrition-guideline-for-overweight-and-obese-adults-with-type-2-diabetes-t2d-or-prediabetes-or-those-at-high-risk-for-developing-t2d. Published August 6, 2020.

IFN Academy. Nutrition Focused Physical. Certification Training Track 3, Module 2. Accessed May 15, 2024.

Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. https://doi.org/10.17226/11537

Layman DK, Anthony TG, Rasmussen BB, et al. Defining meal requirements for protein to optimize metabolic roles of amino acids. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2015;101(6):1330S-1338S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.084053

Lenzi JL, Teixeira EL, De Jesus G, Schoenfeld BJ, De Salles Painelli V. Dietary strategies of modern bodybuilders during different phases of the competitive cycle. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2021;35(9):2546-2551. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000003169

Morton RW, Murphy KT, McKellar SR, et al. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;52(6):376-384. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097608

National Academies Press (US). Protein and amino acids. Nutrition During Pregnancy – NCBI Bookshelf. Published 1990. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235221

Rasmussen B, Ennis M, Pencharz P, Ball R, Courtney-Martin G, Elango R. Protein requirements of healthy lactating women are higher than the current recommendations. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2020;4:nzaa049_046. doi:10.1093/cdn/nzaa049_046

Ross AB, Langer JD, Jovanovic M. Proteome Turnover in the spotlight: Approaches, applications, and perspectives. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2021;20:100016. doi:10.1074/mcp.r120.002190

Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Nutrition and athletic performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2016;48(3):543-568. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000000852

Velzeboer L, Huijboom M, Weijs P, Engberink M, Kruizenga H. How to calculate the protein needs in under- and overweight persons? – NVD. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Voeding & Diëtetiek. 2017;72(1). https://nvdietist.nl/wetenschap/how-to-calculate-the-protein-needs-in-under-and-overweight-persons/